How We Escaped Dev Environment Hell (And Made It Agent-Friendly)

Building a multi-worktree development platform that humans and Claude can both navigate

The Problem: Death by a Thousand Paper Cuts

Every startup has dev environment debt. Ours was getting bad.

The symptoms:

- A

Makefilewith 47 targets, half undocumented, some broken - Three different

setup-env.shscripts that contradicted each other - Devs running with mock API keys, then wondering why integrations “worked locally but not in staging”

- “How do I see the logs?” asked weekly in Slack

- “Which port is the API on again?” followed by someone sharing a screenshot of their terminal

- Postgres running on 5432… unless you’d changed it… and forgot

Then we added Claude Code to the mix:

Every dev now had 2-5 Claude worktrees running simultaneously. Claude would spin up the dev environment, start working, and then… another Claude instance would start the same services. Port conflicts everywhere. Database migrations stomping on each other. One agent’s test run nuking another agent’s seed data.

Then there’s just… the sheer number of services:

Standing up the dev environment means: Postgres (seeded with test data), Elasticsearch (synced from Postgres), Redis, Celery workers, Celery beat, the API, the frontend, email testing, log aggregation, and monitoring. Miss one and something fails silently. Get the startup order wrong and migrations break.

And then you have to replicate all of that in CI. And make it work on everyone’s machine - M1 Macs, Intel Macs, the one guy on Linux. I wanted to cry constantly.

We used to use Supabase. Endless nightmares. Docker + Supabase local dev was a constant battle. Opaque errors, magic auth flows, platform-specific behaviors that worked in their cloud but broke locally.

Here’s the thing I’ve learned: pre-AI, heavy platforms made sense. Supabase, Firebase, Railway - they handled the complexity you couldn’t. Deploys, migrations, dev environments - too much to build yourself.

Post-AI, lightweight composable tools win. Now I can just use:

- Postgres with SQLAlchemy and Alembic (no platform magic, just SQL)

- Celery with state graphs for complex jobs (stored in the database, fully inspectable)

- OTEL for everything (old, boring, standardized)

No vendor lock-in. No platform-specific behaviors. Just well-documented open source tools that Claude actually understands because they’ve been around forever.

Building our own deploys? Claude writes the Terraform. Building our own dev environment? Claude helps debug the docker-compose. The platforms were training wheels. With AI, I don’t need training wheels - I need composable primitives.

Then we moved to VPC:

We put RDS behind a private subnet (correctly!). But now nobody could connect to the database locally. The bastion host existed but nobody knew how to use it. Someone wrote a script, it got lost, someone rewrote it differently.

I spent more time debugging dev environments than building features. Something had to change.

The Human Cost

Here’s a subset of the people on my team:

The frontend dev. Great at React, ships UI fast, doesn’t want to know what an OTEL collector is. Shouldn’t have to.

The cofounder. His main job is sales and customer-facing work. When he codes, it’s rapid in-and-out - a customer reports a bug, he dives in, fixes it, deploys, back to calls. Not deep work. He does not have time to debug why Docker isn’t finding a volume mount.

Me. I built the infrastructure. I understand the Dockerfiles, the Terraform, the VPC topology. Which means every env question lands on me.

The pattern was brutal:

- I’d make an infrastructure improvement (good!)

- Someone would pull main

- “Hey, the API won’t start anymore”

- I’d context-switch from feature work to debug their env

- Find the issue (missing env var, stale container, whatever)

- Fix it for them

- Different person same issue: “Hey, the API won’t start anymore”

- Repeat for a week

Every change to the dev environment triggered a support avalanche. I became the bottleneck. I was scared to improve anything because of the support cost.

And these weren’t dumb questions. “How do I see the Celery logs?” is reasonable. “What port is Elasticsearch on?” is reasonable. “How do I connect to the dev database?” is reasonable. The problem was that the answers weren’t obvious, so every reasonable question came to me.

The frontend dev shouldn’t need to understand Docker networking to see why their API call is failing. The cofounder doing a quick bug fix shouldn’t need to remember the bastion host SSH command. They should be able to be productive immediately and get back to their actual jobs.

The real cost wasn’t my time - it was their momentum. Every “hey quick question” interruption for them was a context switch away from the customer problem they were solving. The dev environment was actively slowing down customer response time.

The Insight: Dev Environment as Product

I realized our dev environment wasn’t a utility - it was a product. And like any product, it needed:

- Discoverability: New devs (and Claude) should find everything from one place

- Isolation: Multiple instances shouldn’t interfere with each other

- Observability: Logs, traces, and debugging tools should be obvious

- Documentation: Not READMEs that rot, but integrated docs

What if spinning up a dev environment was as simple as cd project && make up? What if every worktree got its own URL? What if Claude could navigate it all without asking me?

The Architecture

Traefik: One Port, Many Services

The core insight: use a reverse proxy to route by hostname, not port.

http://supplyco-dev.localhost/api → FastAPI container

http://supplyco-dev.localhost/frontend → Vite dev server

http://supplyco-dev.localhost/docs → MkDocs documentation

http://supplyco-dev.localhost/logs → Grafana/Loki

http://supplyco-dev.localhost/flower → Celery task monitor

http://supplyco-dev.localhost/mailpit → Email testing UI

http://supplyco-dev.localhost/kibana → Elasticsearch UI

Different worktree? Different hostname:

http://supplyco-feature-x.localhost/api

http://supplyco-feature-y.localhost/api

http://supplyco-bugfix.localhost/api

All running simultaneously. No port conflicts. The directory name becomes the hostname prefix automatically via COMPOSE_PROJECT_NAME.

How it works:

# docker-compose.dev.yml (simplified)

services:

api:

labels:

- "traefik.http.routers.${COMPOSE_PROJECT_NAME}-api.rule=Host(`${COMPOSE_PROJECT_NAME}.localhost`) && PathPrefix(`/api`)"

- "traefik.http.middlewares.${COMPOSE_PROJECT_NAME}-api-strip.stripprefix.prefixes=/api"

Traefik reads Docker labels, discovers services automatically, routes based on hostname + path. Zero config per worktree.

The Landing Page: Everything in One Place

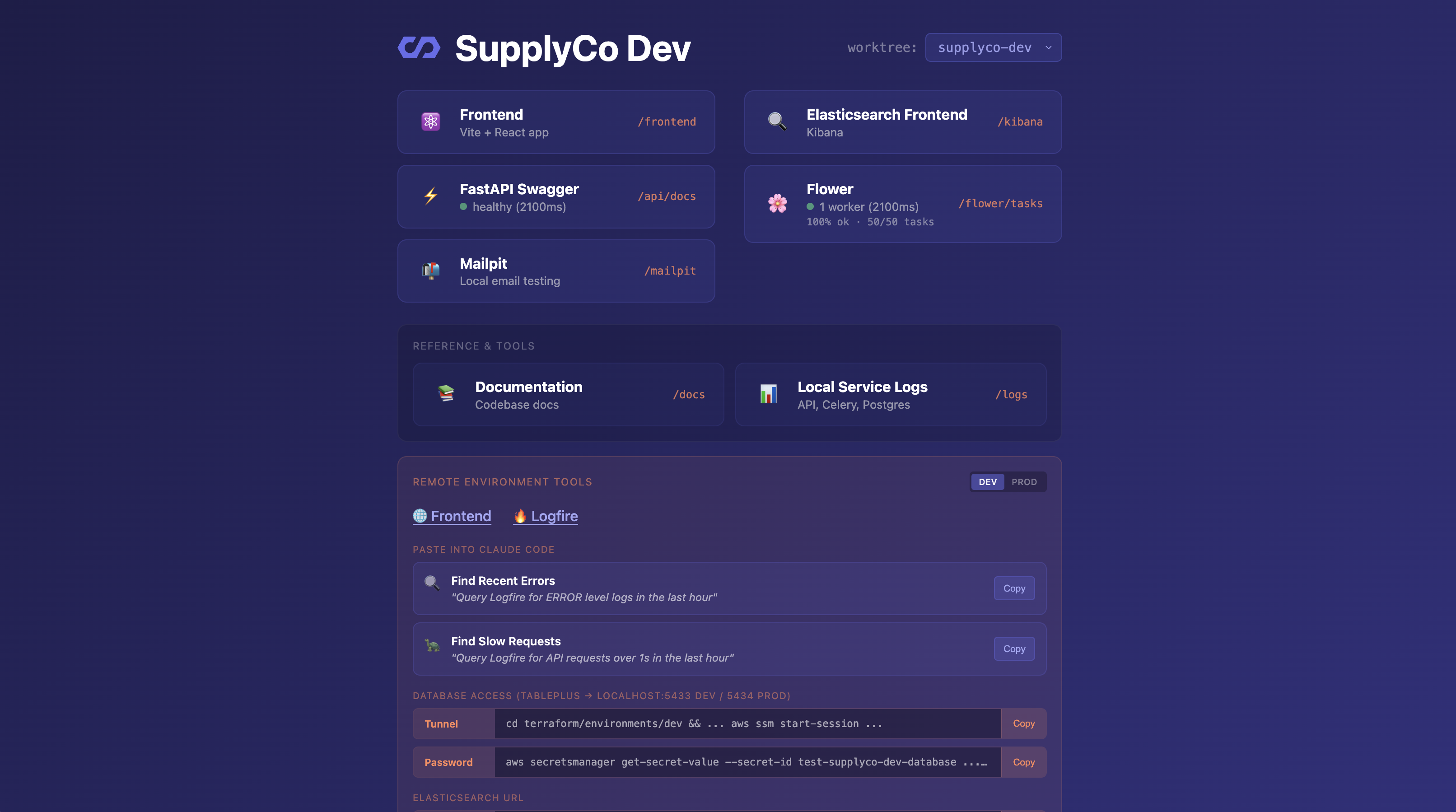

When you visit http://supplyco-dev.localhost/, you get a landing page with:

- Links to every service (API docs, frontend, logs, etc.)

- A worktree dropdown that auto-discovers all running instances from Traefik

- Service health indicators (FastAPI response time, Celery task counts)

- Quick links to documentation

The dropdown queries Traefik’s API to find all projects with running services. Switch between worktrees without remembering URLs.

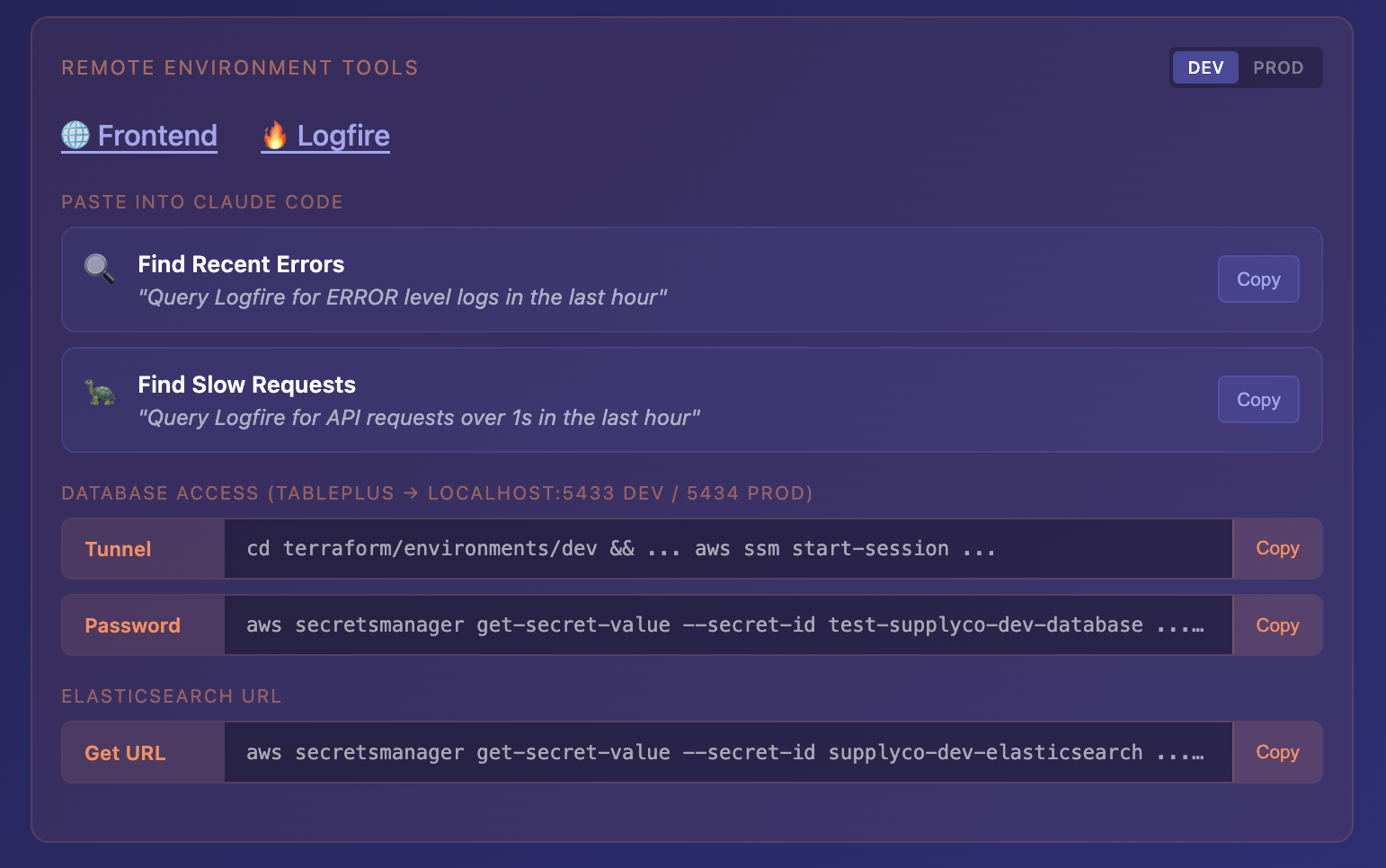

There’s also a Remote Environment Tools section for live incident debugging. DEV/PROD toggle, and pre-written prompts you can paste directly into Claude:

- “Query Logfire for ERROR level logs in the last hour”

- “Query Logfire for API requests over 5s in the last hour”

One click to copy the database tunnel command, one click for the password from Secrets Manager. Production incident? Open the landing page, toggle to PROD, paste the commands into Claude, start debugging. No scrambling to remember how to connect.

Claude loves this. Instead of “what port is the API on?” it just goes to the landing page.

Shared Observability Stack

Here’s the thing about logs: you need them when things break. Which is exactly when you don’t want to be setting up logging.

We run a single observability stack shared across all worktrees:

Alloy (log collector)

↓

Loki (log storage) ← labeled by project + service

↓

Grafana (UI) ← accessible at /logs on every worktree

↓

Tempo (traces) ← for distributed tracing

Every container gets labels:

labels:

- "project=${COMPOSE_PROJECT_NAME}"

- "service=api" # or celery-worker, postgres, etc.

Alloy scrapes Docker logs and tags them automatically.

The key: the /logs link on each worktree’s landing page goes directly to Grafana pre-filtered for that project. Click the link from supplyco-dev.localhost, you see supplyco-dev logs. No query writing required.

No thoughts, only logs.

If you want to filter further, LogQL is there:

{project="supplyco-dev", service="api"} |= "error"

But most people never need it. They click the link, see their logs, find the error. The frontend dev doesn’t need to know what LogQL is. The cofounder definitely doesn’t. They click, they see, they fix, they leave.

One dashboard, all worktrees, all services. No more “which container was that in?” or docker logs | grep.

Multi-Worktree Isolation

The hard problem: multiple worktrees need to run simultaneously without stomping on each other.

Database isolation: Each worktree gets its own Postgres container with its own volume. No shared state.

Port isolation: Services bind to internal Docker network ports, not host ports. Traefik handles external access.

But what about GUI tools? DataGrip, pgAdmin, TablePlus - they need a TCP port to connect. You can’t route Postgres through HTTP.

For non-HTTP services, you have two real options:

-

TLS with SNI routing - Traefik can route TCP connections based on the TLS server name. Each worktree gets

supplyco-dev.localhost:5432,supplyco-feature.localhost:5432, etc. Proper isolation, but requires TLS setup and your tools need to support it. -

Port stealing - One worktree “claims” the standard port at a time. Simpler, works with any tool, but only one active worktree per port.

I was lazy. I went with option 2:

# In worktree supplyco-dev

make expose-this-db

# Now localhost:5432 points to supplyco-dev's Postgres

# Switch to worktree supplyco-feature-x

cd ../supplyco-feature-x

make expose-this-db

# Now localhost:5432 points to feature-x's Postgres

Instant switching. DataGrip config stays the same (localhost:5432). Claude can use psql without port gymnastics. It’s a socat container that forwards the port to whichever worktree ran the command last.

Could I do TLS? Sure. Might I just add pgAdmin or CloudBeaver to the docker-compose and skip all this? Also yes. The port-stealing approach is “good enough for now” - the whole point is I can improve it later without anyone noticing.

VPC Tunneling: The RDS Problem

Moving RDS into a private VPC was the right security call. But it broke local development.

The old way (bad): RDS in public subnet, security group allows your IP. Works until your IP changes, or you’re on coffee shop WiFi, or AWS throttles your connection.

The new way: RDS in private subnet, bastion host in public subnet, tunnel through.

But “tunnel through” meant:

- Find the bastion instance ID

- Get the RDS endpoint from… somewhere (Terraform outputs, technically - but I’ve banned the team from touching Terraform, and none of them have ever used it or entirely know what it does, which is correct and good)

- Run an AWS SSM command with the right parameters

- Hope you got the port right

Nobody could remember it. Nobody should have to remember it. Scripts got written, lost, rewritten.

The solution: One script, multiple environments, automatic discovery:

make db-forward-dev # localhost:5433 → dev RDS

make db-forward-prod # localhost:5434 → prod RDS

The script:

- Gets bastion instance ID from Terraform outputs

- Gets RDS endpoint from AWS Secrets Manager

- Starts SSM port forwarding session

- Outputs connection string for easy copy-paste

Different local ports for dev vs prod means you can have both tunnels running simultaneously. Compare data between environments without reconnecting.

# Connect to dev

make db-connect-dev

# Opens psql session directly

# Or just forward and use your GUI tool

make db-forward-dev

# "Forwarding localhost:5433 → supplyco-dev-db.cluster-xxx.us-east-1.rds.amazonaws.com:5432"

# "Connection string: postgresql://app_user:xxx@localhost:5433/supplyco"

Claude can run these too. Production incident? Claude forwards the port, runs a query, reports back.

The Makefile: One Command for Everything

The Makefile became the API for the dev environment. Every action has one command:

# Lifecycle

make docker-up # Start everything

make docker-up LITE=1 # Skip heavy services (saves RAM)

make docker-down # Stop everything

make docker-down-v # Stop and wipe data

# Logs

make docker-logs # All services

make docker-logs-api # Just FastAPI

make docker-logs-celery # Just workers

# Database

make db-local-psql # Connect to local Postgres

make db-local-migrate # Run migrations

make db-local-reset # Drop and recreate

make db-forward-dev # Tunnel to dev RDS

make db-forward-prod # Tunnel to prod RDS

# Quality

make lint # Fix linting issues

make check # Check without fixing (for CI)

make test # Run all tests

make test ARGS='-k login' # Run tests matching pattern

# Types & API

make api-types # Regenerate TypeScript client from OpenAPI

make check-api-types # Verify types are current

Every target is documented with ## comment so make help produces a useful reference.

No more “let me check the README” or “I think it’s npm run dev or maybe yarn start?” The answer is always make <something>.

Documentation That Lives With the Code

READMEs rot. Wiki pages get lost. Notion docs go stale.

We put everything in docs/ and serve it with MkDocs. And here’s the forcing function: CI blocks your PR unless you’ve updated the docs, or you explicitly add a “skip-docs-check” label.

No “I’ll document it later.” Later never comes. Either the docs get updated with the code, or you have to publicly declare “I’m skipping docs” on your PR. Shame-driven documentation.

docs/

├── architecture/

│ ├── overview.md # System diagram

│ ├── domain.md # Entity relationships

│ └── code-organization.md # Where stuff goes

├── code-style/

│ ├── python.md # Python conventions

│ ├── fastapi.md # API patterns

│ ├── typescript.md # Frontend conventions

│ └── terraform.md # IaC patterns

├── guides/

│ ├── local-development.md # This whole setup

│ ├── database.md # SQLAlchemy, Alembic

│ ├── testing.md # Test utilities

│ └── logging.md # Logfire integration

└── operations/

├── deploys.md # Release workflow

└── incidents.md # Runbook

It’s accessible at http://{project}.localhost/docs - same hostname, different path.

The CLAUDE.md file points here: “Before non-trivial work, read the relevant doc.” Claude actually does this. It’s remarkable how much better the code is when Claude reads the style guide first.

Making It Agent-Friendly

Here’s the thing about Claude worktrees: they’re not just “another developer.” They’re parallel processes that need to be isolated, discoverable, and debuggable.

What Claude needs:

- Discoverability: Where’s the API? Where are the logs? What commands exist?

- Isolation: Don’t step on other Claude instances

- Debugging tools: When something fails, how to investigate

- Context: What patterns does this codebase use?

What we built:

Landing page as entry point: Claude can visit http://{project}.localhost/ and see everything available.

Makefile as API: Every action is a documented make target. Claude runs make help and knows what’s possible.

Logs accessible by URL: Claude can check http://{project}.localhost/logs in a browser, or query Loki directly:

curl -sG 'http://localhost:3100/loki/api/v1/query_range' \

--data-urlencode 'query={project="supplyco-dev", service="api"} |= "error"' \

| jq -r '.data.result[].values[][1]'

CLAUDE.md with explicit guidance:

## Local Development

- Start: `make docker-up`

- API docs: http://{project}.localhost/api/docs

- Logs: http://{project}.localhost/logs or `make docker-logs-api`

- Database: `make db-local-psql`

## Before You Code

- Read docs/code-style/python.md for Python work

- Read docs/code-style/fastapi.md for API work

- Read docs/guides/testing.md before writing tests

Hookify rules prevent common mistakes:

# .claude/hookify-rules.local.md

- Don't import from supabase (we migrated away)

- Use uv, not pip

- Use pnpm, not npm

- Run make lint before committing

Work-in-progress tracking:

We use .claudetext/ for tracking what different Claude instances are working on. Convention: [ ] unclaimed, [C] claimed by Claude, [x] done. Prevents duplicate work.

The Result

Before:

- “How do I run the API?” (Slack, weekly)

- “My migrations are conflicting with someone else’s” (constant)

- “The tests pass locally but fail in CI” (environment drift)

- “I can’t connect to the dev database” (VPC confusion)

- Claude agents fighting over ports

- Me: scared to touch infrastructure because of the support cost

After:

make docker-upand you’re running- Each worktree isolated by hostname

- Logs aggregated and queryable from one place

- Database tunnels are one command

- Claude reads the docs, follows the patterns, doesn’t conflict with other agents

For the frontend dev: He runs make docker-up, goes to project.localhost/frontend, never thinks about Docker. When something’s weird, he checks /logs in his browser. No Slack DM to me required.

For the cofounder: Customer reports a bug. He pulls main, make docker-up, reproduces it, fixes it, make db-forward-dev to check prod data if needed, deploys. Back on a sales call in 30 minutes. Never asked me what port anything is on.

For me: I can improve infrastructure without fear. Last week I changed how we handle env vars. Nobody noticed. It just worked. That’s the goal.

For Claude: Agents spin up isolated environments, check the landing page for URLs, query Loki for logs, read the docs before coding. They’re better at using the dev environment than most humans were before.

The dev environment went from “source of constant interruptions” to “invisible infrastructure that just works.”

The Technical Details

Stack:

- Traefik - Reverse proxy with Docker provider, label-based routing

- Docker Compose - Service orchestration per worktree

- Loki + Alloy - Log aggregation with Docker label scraping

- Grafana - Log visualization

- Tempo - Distributed tracing

- MkDocs - Documentation served locally

- AWS SSM - Bastion tunneling for RDS access

- Makefile - Unified command interface

Key files:

docker-compose.dev.yml # Main dev environment

docker/traefik/docker-compose.yml # Shared Traefik + observability

docker/port-forwarder/ # Port claiming for GUI tools

scripts/port-forward-db.sh # RDS tunneling

docs/ # All documentation

Makefile # Command interface

CLAUDE.md # Agent context

The magic: COMPOSE_PROJECT_NAME defaults to the directory name. Everything keys off that. Rename the directory, get a new isolated environment.

What I Learned

-

Dev environments are products. Treat them like one. They need UX, documentation, and maintenance.

-

Discoverability beats documentation. A landing page that links to everything is worth more than a README that explains everything.

-

Isolation is non-negotiable. Especially with AI agents spinning up parallel environments. Design for multiple simultaneous instances from the start.

-

Observability isn’t optional. You will need logs when things break. Make them easy to access before things break.

-

One command per action.

make docker-upis infinitely better than “run this, then that, then set this env var, then…” -

Agents need the same things humans need - just more explicitly documented. CLAUDE.md isn’t extra work, it’s documentation you should have written anyway.

Getting Started

If your dev environment is in the “47 Makefile targets” phase:

-

Add a reverse proxy. Traefik with Docker labels is ~50 lines of config. Suddenly you have URLs instead of ports.

-

Add a landing page. One HTML file that links to all your services. Put it at the root route.

-

Aggregate your logs. Loki + Alloy is free and runs locally. One dashboard instead of

docker logsacross 10 terminals. -

Document commands, not concepts. Your Makefile should be the entire interface.

make helpshould answer most questions. -

Write CLAUDE.md. Not because you’re using AI, but because explaining your environment to an agent forces you to make it logical.

The best dev environment is one that makes the next person (or the next Claude) productive immediately. Everything else is just complexity.

Our setup is specific to our stack (Python/FastAPI/React/AWS), but the patterns generalize. The goal is: clone repo, run one command, be productive. If your env requires more than that, you have work to do.